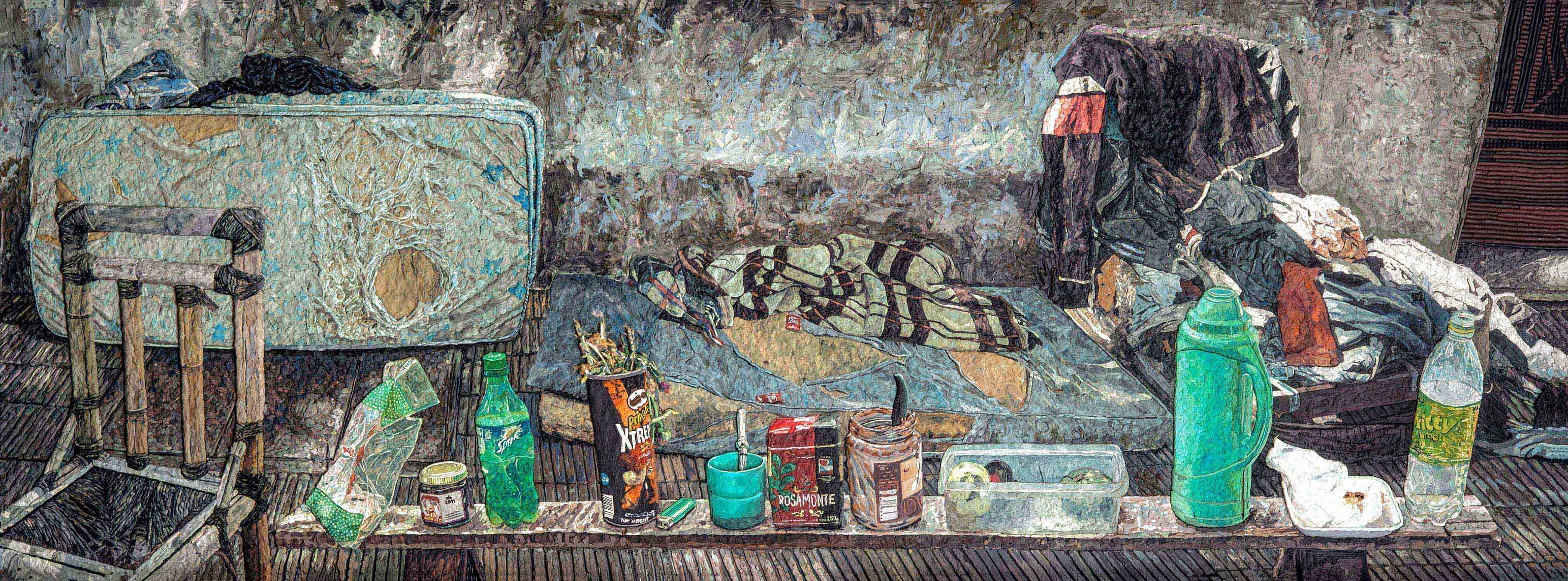

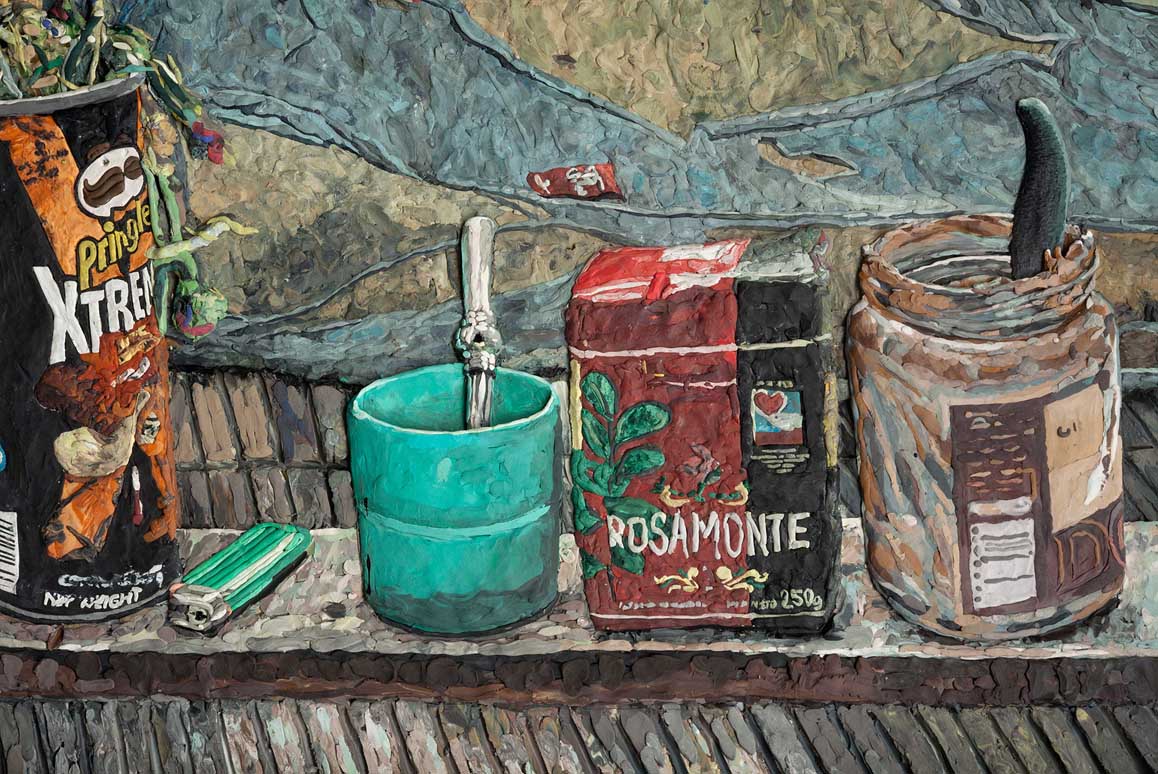

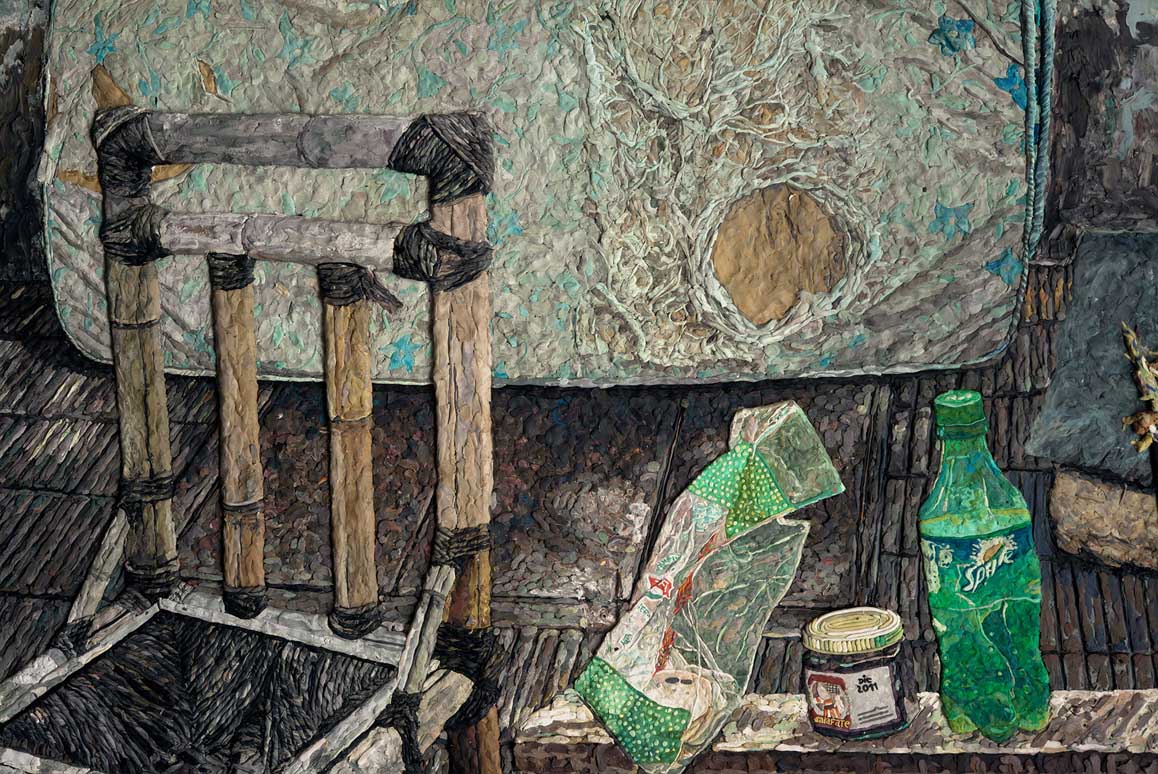

STILL LIFE

Still life played a fundamental role in Modernism but tended to disappear in Postmodernism. Let us think of the role it played in the works of Braque, Picasso, and Gris, which was instrumental in defining Cubism. Let us think of Morandi and the way he used it as a vehicle for human emotions, for solitude or the need to touch, for the will to mix and unite, and for the simple or not so simple, overwhelming evidence of divisions, separations, and differences in life. Let us think of how Caravaggio places a still life of apples and pears in Supper at Emmaus; of how Picasso painted them for seventy-five years; or how Van Gogh did not hesitate to propose such a simple gesture as a Still Life with Onions. All of these works spoke of much more than meets the eye. Guy Davenport argues that still life has always dealt with the place where matter ends and spirit begins, and with the nature of this interdependence.

The Mondongo(s) seem to have understood still life as a genre capable of even leading us toward the perverse and problematic consequences of globalization and a lifestyle based on consumption, which they seek to represent as the reality of some and as the bitter dream of others.

—Kevin Power, 2013

Naturaleza muerta, 2011—2012